Note: this article is a chapter from Juraj Bednar's book "Cryptocurrencies – Hack your way to a better life.

Why use cryptocurrencies as payment networks at all? After all, Bitcoin transactions are often expensive and relatively slow - although Bitcoin is still useful as hard money for saving. Why even bother with any payments for hipster flat whites and when making payments over the Internet?

My primary reason is privacy. There is nothing worse for privacy than paying with a credit card through a payment provider. You lose privacy in several areas right away. Your bank knows everything about you, or they wouldn't give you a credit card. When a Swiss banker did the KYC (Know Your Customer) process with me a few years back, he started by saying "this is going to be awkward, I'll probably ask you your shoe size and how often you have sex. Just answer yes and no, I don't really care about those answers, it's just because of the form and the regulations". The bankers (or the crypto exchangers that do KYC) don't really care about my personal information. They make money from the fees I pay them.

However, the situation is even worse in the rest of the payment network. There are several actors there who are interested in the information for other purposes. I mentioned that PayPal lists more than 600 partners with whom it shares data about your financial transactions. If you think it's a good idea to pay with cryptocurrencies with an "exchange app," I don't recommend it.

But what few people know is that cryptocurrency exchanges that know personal information about you share it with companies that provide so-called "blockchain analytics." They match (likely) wallet owners to transactions. One of the reasons they do this is to prevent trading in stolen cryptocurrencies that the exchange shouldn't convert into euros, dollars and other fiat currencies. The problem is that there is always a clause in the contract with such companies that the exchanges must in turn share your transaction data with the analysis company. So if you "pay" from the KYC of an exchange to make a purchase, that information is available to all customers of the blockchain analytics firm that the exchange uses - and we don't know if and to what extent these firms share the information with each other.

The consequence of this is that your identity "follows" you around the blockchain. While it is not directly stored in it, this does not mean that your purchasing behaviour is anonymous from the moment the cryptocurrencies leave the exchange. On the contrary, it is tracked and you don't even know exactly who is tracking you.

Due to the value of the data flowing through them, payment networks are a huge surveillance system from which private companies and public institutions (tax authorities, financial police, etc.) pull data.

A lot of people will say "but I have nothing to hide". Spy systems should always be looked at from the perspective of the worst case scenario. If we lived in communist Czechoslovakia, would you want the state secret police to have this information virtually instantly and on everyone? There are many examples of turns for the worse - Nazi Germany (first collecting information on Jews and then introducing repressive measures), Iran, North Korea, etc. Technological developments and the fact that we live in a liberal democracy give us the illusion that history only goes in one direction - from worse to better. In reality, however, the process of change is more stochastic and leaps for the worse are not rare. That is why, with every spy system, imagine that all the information is seen by your worst political enemy, who has a constitutional majority. And with this optic, let us look at the various payment systems.

From this point of view, it is probably best to use cash, but it is more difficult to send it over the Internet. Therefore, if you want to cultivate true peer to peer relationships, without sending information about your financial transaction to dozens of institutions, it is a good idea to at least use cryptocurrencies that you buy anonymously when making purchases over the Internet. At the time of this writing, you can do this in a variety of ways - for example, through Bitcoin ATMs or through exchanges that do not have your personal information, such as Bisq or HodlHodl. For a better list of exchanges and merchants that don't do KYC visit, for example, the kycnot.me. Of course, you can also buy cryptocurrencies from someone else who sells them - just for cash.

Payment cards are probably the worst in this respect because not only do they not conceal the identity of both parties, they also contain information about the transaction. The organisations that get your data know how often and for how much you shop at the supermarket (and which one), how often you order supplements over the Internet, and so on. In most banks, every bank employee has access to this data, although this access is monitored. And so you sit down at a desk in a branch with a bank employee, and the employee, in an attempt to sell you more products, goes through your account statement, entry by entry. He finds out that you're paying a competitor's credit card company, how much you're paying for life insurance, and so on.

Why is KYC a risk?

First of all, there is the possibility of leaking your personal data, which often goes much further than just your name, residence and date of birth. Institutions gather additional knowledge from your behaviour so that they can assess the risk of you as a client. If this data is leaked, it's a serious invasion of privacy that can cost you directly - in 2018, the direct cost of identity theft in the U.S. was $1.7 billion.

The leakage of personal data does not only have to occur directly at the institution to which you give your personal data. Under the OECD CRS, information about your balances must be shared with the tax authorities of the country where you are tax resident (usually evidenced by a "utility bill" or "proof of address"). This applies to all financial institutions involved in international payment networks (banks, payment service providers, and yes, even all crypto exchanges that can withdraw and deposit fiat) in all countries that have signed the international Common Reporting Standard treaty - which is basically all countries reachable via payment networks except the US. But the US has its own FATCA reporting scheme.

Since it is better for financial institutions to "overcomply" (i.e. go above and beyond what is actually required), if you have a Slovak passport and live in the Czech Republic, many institutions will send the information that you have an account with them, your balance, etc. directly to both Slovakia and the Czech Republic. This information then ends up in a computer database of both tax offices and there are local bureaucrats that have access to this database. This data should theoretically be well protected, but this is purely theory. For example in the country where I'm a citizen – Slovakia – even very sensitive medical data on people tested for COVID-19 has been leaked. And that's only a leak by hacking! What if someone went to an administrative official, put ten thousand euros on his desk and said "I want information on all the people who have an account on a bitcoin exchange" or "have a balance greater than a million euros". Do you think the official would have resisted? Would they all resist or would there be at least one who gives in to temptation?

A lot of people will say that sensitive data will only leak in underdeveloped countries, but it cannot happen in advanced countries. In 2020, the US anti-money laundering agency FinCEN leaked a number of reports of suspicious transactions. These are more than 2,500 documents on transactions from 2000 to 2017. In fact, banks are required to report any suspicious transactions. This gives them partial immunity from having to do financial policing. If it was suspicious and they reported it, it is the job of the financial authorities to investigate whether it was legal. That doesn't mean they prevented those transactions. If they did report them and the authorities acknowledge that they should have prevented them, they avoid prosecution precisely because they didn't hide them.

Here it is important to note that banks are incentivised to report transactions that look "strange", i.e. it is an unusually high amount or it is a transaction between unusual or “risky” countries. This does not mean that any reporting is automatically an unfair transaction. So there are plenty of normal legitimate transactions among the documents. The people and especially the companies that sent them did not know they were being reported and their transactions are suddenly public because the authorities failed to protect them.

However, you can protect yourself from leaks by not giving the information to anyone.

What can also happen is that you might accidentally get on some (rather poor quality) list of people at risk. People have been listed because someone with a similar name posted on some weird forum or some tabloid made up an article about them. If someone is doing a background check on you, they are very often checking to see if you are on such a list. Financial institutions have to protect themselves – they need to keep their banking license. It is very difficult to get off such a list, and often you will not even find out that you are on it, only that the financial institution will tell you that it cannot do business with you, and that this is a business decision by the bank that cannot be disputed.

Another risk is a situation similar to Executive Order 6102, by which U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt confiscated gold from its citizens. If you tell a financial institution about your transactions, the financial institution can (under a law that parliament or congress can pass at any time) obtain information about your transactions. And it will use that information to figure out who bought what and what it can confiscate.

So what is the solution? To also perceive the privacy that the payment network gives and takes away. Use cash, at least for "sensitive transactions," and pay over the Internet with cryptocurrency payment networks that you enter anonymously using cash.

Risks of no-KYC exchanges

Decentralized exchanges also have their risks. There is the possibility of getting coins with a "strange" history (maybe it is optimal to send them straight to a mixer like Wasabi or Whirlpool). Or you can use an anonymous cryptocurrency that doesn't have this problem. Better yet, use the Lightning network to receive it, where you control the history of your coins (the coins you receive are on-chain represented by the transaction used to open the channel).

Another problem with some exchanges may be a strange fraudulent scheme to send fiat. This is something that many decentralized money changers try to prevent in various ways - by reputation, or by special marking of payments to make it clear that it is a purchase on the exchange and not a loan or something similar.

For cash transactions, you need to be wary of counterfeit notes (as with any cash transaction) and of legal cash limits. Less is sometimes more.

Privacy of individual cryptocurrencies

Different cryptocurrencies have different levels of privacy. Ethereum-based cryptocurrencies have very low privacy because all payments typically come from a single account from which fees are also paid. Thus, at a click, a person can see all of that person's transactions on the Ethereum blockchain.

Cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin, Litecoin or Bitcoin Cash have a slightly better model based on the so-called UTXO (Unspent Transaction Output). Each user uses a different address for each incoming payment (although one address can be used multiple times, this is not recommended and wallets by default always generate a new address if they already see an incoming transaction at an existing address). Individual addresses can be linked, but this can be prevented to some extent. It is also relatively easy to use so-called mixers that try to remove transaction history using various techniques - the most well-known are Samourai Wallet and Wasabi Wallet.

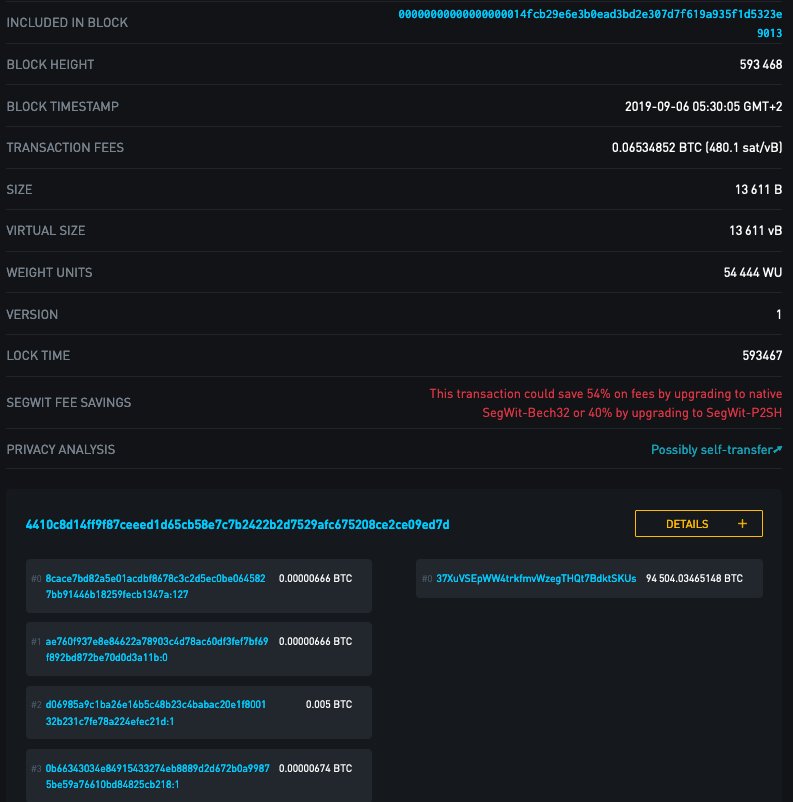

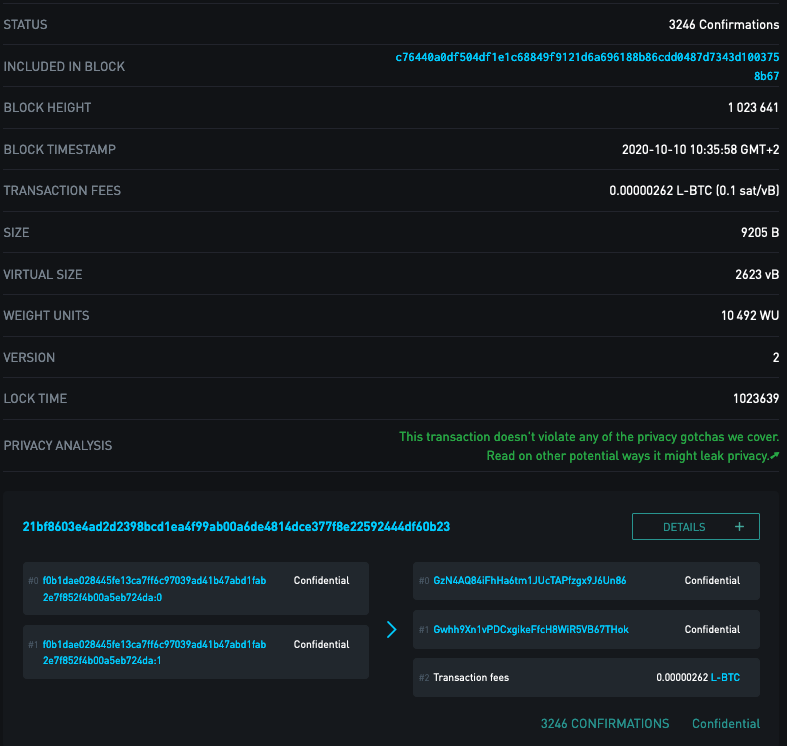

We can see the transaction in the Bitcoin network, for example, this transaction moved over a billion dollars worth of Bitcoins.

We can see the addresses from which the transaction left, the address where it arrived, the amount and the fees. If we look at the Liquid network, we don't see the amounts, only the addresses (this particular technique of hiding amounts used here is called "Confidential Transactions").

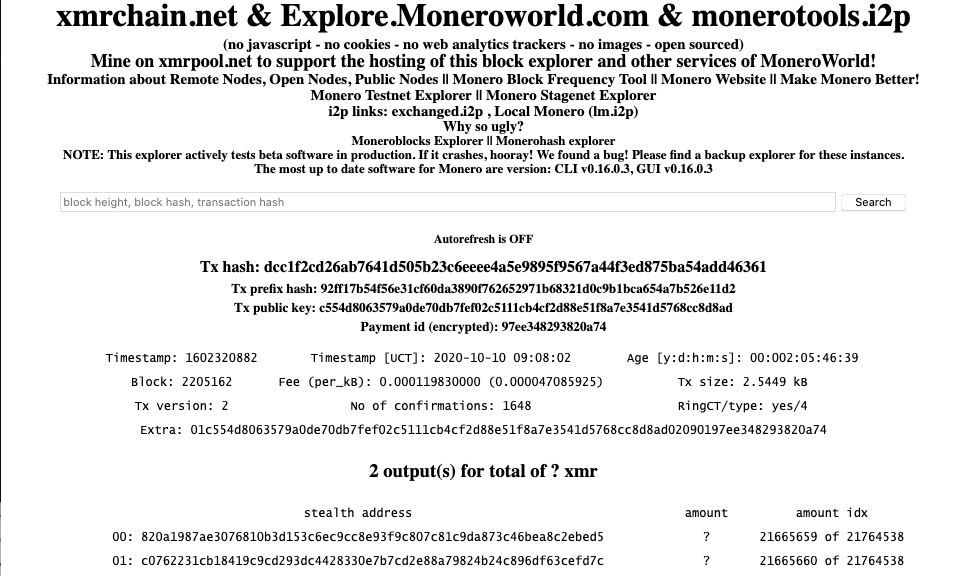

Cryptocurrencies that are more privacy-oriented, such as Monero, try to hide both addresses and amounts.

For anonymous cryptocurrencies, not only the technique is important, but also the so-called anonymity set. When I walked around Bratislava in 2019 wearing a black face mask, although my face was not visible, I was easily identifiable. I was the guy with a black face mask. In 2020, a large number of people are walking around in black face masks and it is more difficult to distinguish us from each other. Cryptocurrencies like ZCash have the ability to swap classic auditable coins, which work the same as Bitcoin, for hidden coins, which are mathematically fully interchangeable. However, if only few users actually use the feature, if someone swaps 0.1 ZEC for anonymous coins and three hours later 0.1 ZEC comes out of the anonymous pool to a different address, it's not hard to figure out that it's probably the same user. With respect to the anonymity set, it is thus a very good property that anonymity is mandatory in a given cryptocurrency - any transfer increases the size of the anonymity set. In addition, if there is no visible amount, a potential attacker must examine all transactions, including uninteresting "few cent" transfers, because there is no way to distinguish whether someone is moving ten cents' worth or ten million dollars' worth of cryptocurrency.

In the Lightning network, the privacy model is completely different than on the blockchain. Payments do not have a permanent record, they only change the balances of individual channels and are truly "peer to peer". This means that for a Lightning payment, the sender, the receiver, and the operators of the nodes through whose channels the payment passed know about that payment. No one else. And no one knows if it is the full amount or only part of the payment (a single payment can be divided into multiple routes through channels) and if the other side of the channel originated the payment or if it is just routing a payment for someone else.

It is interesting to combine payment networks. For example, using decentralized or instant exchanges, you can create a Bitcoin transaction using Monero payments. Or use Lightning Payments to create a Bitcoin on-chain, Litecoin, Bitcoin Cash or other transaction. For a demonstration of how to make such payments, see my course How to use the Lightning network to make payments in Bitcoin between friends and for goods and services. If you anonymize your Internet connection, for example by using the Tor network or by using a VPN, there will be no connection to your other activity in the blockchain history - in fact, the money that is sent in the target payment network belongs to the exchange (or the other party that did the exchange) and has nothing to do with you. So you have created a simple "I pay you via lightning and you send another cryptocurrency for me" contract. The permanent footprint in the blockchain thus goes to the exchange.

Comparison with the privacy of other payment networks

Other payment networks such as credit cards are tied to a name. Often a billing address is required, which is sometimes verified.

Since payment card security is based on knowing a few numbers (card number, expiry date and CVV) that are passed on to third parties, it is a good idea to verify some of the data that is not printed on the card. Some data are forbidden to be stored by the operators (CVV). Some payment gateways verify the billing address. This reason is largely redundant with the advent of 3D Secure payments or services like Google Pay and Apple Pay, payments are verified based on another factor (e.g. SMS or confirmation in the card issuer's app).

The billing address is also used for risk assessment. If you are accessing from a Russian IP address, but the card is issued and used in Slovakia, there is a high probability that it is a theft and the payment network will often reject such a transaction.

Cryptocurrencies solve these problems by making transactions electronically signed and irreversible. The provider does not need to know the identity of the client to make a payment at all, and also does not have to worry about chargebacks or fraud. If the payment is confirmed in the network, the merchant can be 100% sure that he has received the money irreversibly.

Another reason for decreased privacy is that the provider of products or services needs to charge the correct VAT. As many people realise that, especially for electronic services, it is enough to select "I am from Hong Kong" (Hong Kong does not have VAT), some providers verify the billing address with the card issuer so that it is not so easy to bypass paying VAT.

Other fiat payment networks are in a similar position with privacy. However, it is not only the retailer and the payment network that obtains information about the customer's personal data. As I mentioned above, PayPal, for example, has terms and conditions stating that it can share your personal information with over 600 entities. Regulations such as the OECD CRS, FATCA and so on even impose an obligation on every provider of banking, financial and payment services to automatically inform the tax authorities. Anti-money laundering regulations in turn force them to block transactions or inform the financial police. All of these information shares are automatic once certain conditions are met - it's not a case of 'after all, I'm making a small turnover' or 'I'm not doing anything wrong'. This data is sent, processed and retained for a long time.

The first and fundamental problem with automatic data sharing is - can the recipient protect it? The recipient is often a government institution. And we are talking about a technical hack; the second and much more likely attack vector is simply buying the data from an employee who has access to it. But government institutions are not the only recipients of data - there are also marketing firms, credit bureaus, and the like. Imagine that when you make a payment, an information firework is set off that sends out information about that payment to various third parties with whom you don't automatically have a voluntary relationship.

Another problem is that the payment network operator is very likely to know your entire buying behaviour - what you buy and where you buy it. Especially in Slovakia, after the introduction of the eKasa system, information is stored in a database accessible from the Internet not only about where and for how much you bought, but also exactly what items you bought. The information that you have printed on the receipt will be sent directly to the Financial Administration. Of course, the receipt (unlike an invoice) does not directly state your identity - but when you pay by card, it is possible to match the identity to the receipt (by terminal and amount).

In addition, this information is stored in the systems for a long time. I personally find it very annoying when a bank employee digs into my account movements in an attempt to sell me other products. It is clear to me that any bank employee can theoretically see all my account movements and get quite a lot of sensitive information. And not only theoretically. There is a well known case in my country where a bank employee, Filip Rybanic, abused this to leak private bank information about a politically exposed person’s account. In this case, however, the court found the bank employee guilty of a criminal offense.

Thus, classic payment networks are the worst possible from the point of view of privacy - they show not only when and for how much, but also where I bought (name of the store, location of the terminal).

It is important to understand that we do not need to know the identity of the customer to provide most products and services. We are sometimes forced to do so by regulation, but it is not necessary for the actual provision. If I am selling virtual servers, phone number services, domains, web addresses, access to software as a service, an e-book, an online course, and so on, I don't need to know the customer's first name, last name, and address at all. And if I don't have that information, I don't need to protect it.

Cryptocurrencies do not automatically carry an identity with the payment. I don't need to know your email, first name, last name or address to create a cryptocurrency account. A wallet-signed transaction is all I need to make a payment. Cryptocurrencies thus make it easier to comply with government regulations such as GDPR - if I don't have personal data, I don't have to protect it.

From this perspective, cryptocurrencies preserve both the privacy and security of the payment at the same time.

Travel rule

However, the invasion of privacy is making its way into cryptocurrency payment networks as well. The story of financial regulation is a complicated one, but I think it is a very interesting one. Most people think that the way that anti-money laundering regulations and many others are created is probably like this - officials (of the European Union, for example) sit down with experts, try to come up with sensible rules, and then put those rules forward as a proposal to be debated by a commission and later the parliament. This gets approved and then the parliaments of the individual EU countries adopt it into their legislation. This is the visible part, which comes after the rule has been in place for a long time. So what is the reality?

It works like this. FATF-GAFI, a non-profit and non-governmental organisation, issues "recommendations" to combat money laundering. It also produces "watch lists" of countries or organisations that are not doing enough to combat money laundering. If a country or organization wants to show that it is fighting money laundering, the country or bank in the payment network accepts the FATF-GAFI "recommendations." Since this is the consensus standard of the majority in the payment network, if an entity wants to participate in the payment network, it must somehow prove that it is fighting money laundering.

This is most easily demonstrated by implementing their recommendations as rules - and following and enforcing those rules on other partners. The European Union's AML5 is the implementation of the FATF-GAFI recommendations into a coherent legal framework. Many of these rules were already being enforced by banks and countries before regulation was ever adopted, because if someone wanted to send money to the US, for example, the correspondent bank would ask them what they were doing against money laundering. And the easiest thing to do is to show 'we are implementing this standard'.

That is, the adoption of rules in the banking network goes the other way around - it arises through mutual coercion in the banking network and then gradually translates into written rules. Let us note that the regulation of the banking network is done by a non-profit, based in the OECD building in Paris, which is not elected by anyone and has no official legislative power. Yet it can write rules that the whole world follows - not just members of the OECD, the EU or any other entity.

The FATCA and OECD CRS regulations were adopted in a very similar way - they were "virally disseminated through the network effect". Simply in a "if you want to do business with us, you have to follow these rules" way.

FATF-GAFI has a second role - enforcement, which "monitors money laundering". So, for example, they will find that Panama has not directly implemented the FATF-GAFI rules into law, but has fought money laundering in its own way. The result was that in 2019, Panama was put on a "watchlist" of jurisdictions that are at risk from a money laundering perspective. They didn't get there because they were proven to have laundered money in specific cases, but because they chose to fight money laundering in a different way.

What does it mean? Anyone following the FATF-GAFI recommendations must specifically screen all transactions with Panama. This slows down international trade, which is why Panama has done everything it can to get off the watchlist – FATF-GAFI has practically put a law on the table for MPs to pass. The OECD CRS rule has been extended in a very similar way.

What does this have to do with Bitcoin? One of the FATF-GAFI "recommendations" is to "tag" cryptocurrency transactions. If a transaction is worth more than $1000, it should somehow verify the identity of the sender and communicate it to the other party. This information does not need to go directly through the blockchain. Protocols have started to emerge that allow such an exchange of personal data.

The first to follow this rule are the exchanges that support deposits and withdrawals in government fiat money. These need to be plugged into the classical financial network for their business. The FATF-GAFI travel rule has already been adopted and is being enforced through the financial system, regardless of whether it has been approved by national or EU parliaments.

These rules are now being extended to other VASPs (Virtual Asset Service Providers – a new term introduced by FATF-GAFI), which include wallet providers, payment gateways and practically everyone who is touching crypto in any way. And one of the “recommendations” to be implemented is to make sure that VASPs only accept cryptocurrency transactions from wallets of other VASPs. So “self-hosted” or “anonymity enhanced” wallets are to be considered of high risk of money laundering and should be “considered” deeply. Because investigating transactions is often not profitable, this is a “nicely sounding” ban. We will see how exactly it will be implemented.

How does this enforcement work in practice? An illustrative thought experiment:

- We declare that "untagged" BTC transactions are used for money laundering

- We will create a standard for transaction tagging

- Banks, exchanges and the like will start implementing this because they don't want their partners in the fiat payment network to close their accounts or disconnect them from the payment network

- FATF-GAFI monitors which countries and which institutions do and do not comply

- If a country ignores this (and thus is not "in the cartel"), they declare them a "money laundering center" and put them on a watchlist

- This makes it much more difficult for them to interact with traditional financial systems of the world. The watchlist is global for all transactions, so if someone does not want to implement a travel rule for cryptocurrency transactions, the consequence is a restriction of access to international trade overall - the watchlist does not just apply to one segment. The country is very likely to say "screw some few Bitcoin traders, let's enact this because we don't want to be on the watchlist".

- FATF-GAFI and the consultants will supply the exact wording of the law, which they will translate into the local language and correctly paraphrase the sections of the “recommendations”. Members of Parliament pass the law in Parliament, basically unaware of what it is and how it came about.

- FATF-GAFI will add a press release to its website on its successful cooperation with another country and will issue a case study on how it has curbed further money laundering.

Every deposit and withdrawal from the exchange will therefore be marked with our identity - name, surname, address, residence, etc. That "innocent KYC data" that used to be collected and shared with chain analysis firms or under court order at most will become part of our transactions - by the way, this data can be populated retrospectively as well, since they knew your identity when you made withdrawals and know which transactions are withdrawals of your funds. This is if you went through a KYC exchange.

Dystopian vision of introducing financial tracking into cryptocurrencies

In time, states may force merchants to accept only cryptocurrencies marked as such. If a person wants to use cryptocurrencies to pay for anything legally, anonymity will be gone. And so the individual cryptocurrency "coins" will be divided into legal (marked with an identity) and illegal, which will be unusable for legal purchases. I don't mean that some cryptocurrencies will be legal and some won't, but the balance in the wallet will be marked and unmarked. Think of it like banknotes, some are stamped and you'll be able to use those to buy at the grocery store or hipster cafe and unstamped ones that will only be usable in the grey and underground economy.

Technical solutions to increase privacy would be unusable in such a case - coinjoin or other mixing and privacy-enhancing methods would simply turn the cryptocurrency units into unmarked ones. Using this mixing technique would be linked to our identity, so we would very likely be visited by some financial authority asking why we put our money in an anonymizing tool.

I think an even worse thing than not regulating or banning cryptocurrencies (which everyone thought was the worst case scenario, with the result "crypto can't be banned") would be to legalize it. And only legal, stamped crypto will be allowed to be used.

Why bother with cryptocurrencies then, if this is a possible scenario in my opinion? In fact, such a dystopian future is already well established in the fiat world. Cryptocurrencies are internet protocols that allow privacy and can play the role of digital cash even in a parallel economy (see appendix). Cryptocurrencies are therefore getting better from a privacy perspective and allow for a parallel economy without surveillance - and this is their advantage even if "approved" uses continue to be monitored.

We already see the first steps towards this dystopian future in the current FATF-GAFI recommendations proposal.

About the book

This text is a chapter from my book Cryptocurrencies - Hack your way to a better life. You can get at it:

- English ebook and paperback on my store

- English ebook and paperback on Amazon

- Spanish version: my store or Amazon

Use coupon FREEDOMTECH for a 10% discount on my store.

Join the Conversation

If this post has sparked an idea or motivated you to get involved, there is no better next step then to join the conversation here at freedom.tech! Subscribers can jump straight into the comments below, or you can join our community SimpleX or Signal groups:

If you have feedback for this post, have something you'd like to write about on freedom.tech, or simply want to get in touch, you can find all of our contact info here: